The core question for the Buddha was the reality of suffering, and how and why it brings misery to our lives. After his enlightenment he formulated his understanding of this in terms of Four Noble Truths. They are found in every general introduction to Buddhism and students generally accept them uncritically as the core of the Buddhist teachings. However, I find such a reaction extremely unsatisfactory because it takes only a little scratching beneath the surface to discover they don’t fit modern thinking at all. The suffering of conditioned existence is not on our radar; the idea that all our suffering comes from our minds is really wild; and the claim that there is a way to transcend the human condition altogether so human beings can somehow become more than human beings without any robotic enhancement, is off the charts. None of these ideas compute for most of us and we cannot simply take them in our stride. It’s essential to face up to the fact that the Four Noble Truths are asking us to jump out of our box.

When the Buddha left his father’s palace in search of a deeper meaning to life, he was not looking for happiness. As a young prince he already had access to all the forms of happiness and pleasure that one could possibly wish for. Instead, he was looking for truth. The truth about life, about the sufferings of illness, old age and death that plague everyone, about why people are generally so unhappy and what can be done to turn that around. His logic was based on the premise that only knowledge has the power to change things and bring about freedom. Unless one understands reality thoroughly, the result of whatever one does to solve problems and relieve pain will be short-lived or fail altogether because one’s action is based on shaky ground.

He spent some six years in the forest engaging in a variety of practices in search of this truth. Meditation, yoga, testing the limits of the body through deliberate hardships, all of these taught him certain valuable things but were not enough. In the end he found enlightened insight by combining calm abiding meditation (shamatha) with insight meditation (vipasyana). He gave his first teaching several weeks after his enlightenment, and in that teaching he revealed the supreme wisdom he had realized. This is known as the Four Noble Truths or the Four Truths of the Noble Ones. The truths themselves are not noble but they are recognized by ‘spiritually noble’ beings.

In a nutshell, the Buddha asks us to recognize that the nature of all existence is suffering. Even happiness eventually comes to an end and then causes distress and disappointment. And all our suffering is caused by our own minds. Self-centred emotions, habits and tendencies lead to harmful actions and these two – mental afflictions and the actions they instigate – bring about the many facets of misery and pain with which we are familiar. At the same time, he assures us that it’s possible to transform the mind; we can eradicate the causes of suffering and in that way bring the experience of suffering to a complete end. Our mind is then totally free of all causes and conditions; it is able to know ultimate reality. These Four Truths – suffering, its causes, its end and the methods to reach its end – are the blueprint for the entire corpus of the Buddha’s teaching.

From this summary we can see how different the enlightened perspective is from the way we generally see the world. It’s tremendously challenging to go, or try to go, beyond conventional and conditioned reality when we come from a living environment in which conventional reality feels all-powerful. It has become so deeply accepted and ingrained in us all, and its materialist values and views have become so widely assumed, that most of us think that conventional reality is all there is. Furthermore, the mind, which is clearly crucial to the logic of the Four Truths, has been relegated in the contemporary world to the status of second-class citizen. In contrast to this, the Four Truths present both the conventional world and the transcendence of that world; the experience of suffering and freedom from suffering; as well as the methods that lead from the one to the other. The Buddha shatters the glass ceilings of what is humanly possible.

For me, the most significant move that the Buddha made lies in his identifying the causes of suffering as being mental. They are about the way we think, and the way our habitual patterns and uncontrolled emotional responses lead to harmful actions. Generally we consider that the causes of misfortune are external. We point the finger at other people, especially family and partners, we blame people in any position of power, we accuse governments and billionaires; we think the ‘system’ is at the root of all wrong. Some people believe that suffering is a form of divine punishment which comes from outside of us and is beyond our control. By shifting the causes of misery to ourselves the Buddha opens up a space that empowers us human beings to change and transform and re-invent the future. He taught that once the mind is freed of its conditioning and constraints it is naturally bright and wise and loving. This perspective is really the bedrock for a spiritual process that has the capacity to bring transcendental results.

Taken together, these four Truths can bring a sense of hope to people who otherwise see no reason to be hopeful. In modern societies there is an epidemic of self-doubt and lack of self-worth, where we do not feel good enough. Unless we’re fortunate to find circumstances that help us find true confidence – not just bravado – then we will see ourselves as hopeless cases for whom there is no such thing as a bright future. On top of this, there is a pervasive view in the modern world that human nature is no better than that of wild animals, meaning that without cultural norms human beings descend rapidly to the level of barbarians and thugs as depicted, for instance, in Lord of the Flies. This is a dismal perspective and one that gives no conceptual basis for trying to change for the better. And right now, human beings are confronted with the prospect that humanoid robots might carry out their work and profession better than they can themselves, leading to serious life crisis. After all, without a spiritual perspective a life without work can feel meaningless. And the film The Beast takes this prospect even further and imagines that in the not-so-distant future robots will be considered intrinsically better than humans because they don’t have the cognitive distortion that prevents us from seeing clearly and making the best decisions.

The Four Truths open up possibilities and prospects that are simply not on the horizon for most people. I have met countless people who are effectively stuck with how they are and how their life is because they have never been introduced to the idea that fundamental shifts are possible. I had a good friend who lived in a beautiful house in Oxford. His work was devoted to helping physically handicapped people use computers. He was a family man with a wife and two children and on the face of it one could have said his life was good. But I knew him well and I was aware he was frustrated with his life which he found too comfortable and routine. He was longing for freedom and adventure but had no way of accessing either. When bad things happened to his friends or himself he was resigned and accepted them as part of life. Resignation can be wise but, in his case, it was also a sign of defeat. The freedom he longed for was beyond his reach and he had no idea there was a way of breaking out of the cocoon. I would say that his lack of vision was his greatest pain. And how many millions more are in the same predicament.

The Four Noble Truths counter all these cultural views, and simply hearing that it’s possible to break free from the grip of our pain can be a healing balm.

Samsara and nirvana

The Buddha is saying that the experience of suffering can become the starting point of a spiritual life. If we did not suffer at all we would not ask ourselves deep questions about life like what the causes of suffering are, or what methods could succeed in ending it; nor would we be in search of meaning. It is when we undergo painful experiences that we ask ourselves ‘why?’. Why is this happening to me? Why do I have to go through this? Why did things go wrong? We instinctively look for an explanation for our predicament. Similarly, unless we have confidence that the cessation of suffering is possible, a confidence that is gained through listening to the teachings, reflecting upon them and meeting spiritual people who inspire us, then we will not be motivated to follow a path at all.

The first pair of truths describe what is called ‘samsara’ while the second pair of truths describe what is called ‘nirvana’. Samsara is the Sanskrit term for conditioned existence characterized by sufferings of all kinds, the dimension of existence that is subject to causality and therefore not free. Nirvana is the Sanskrit for the profound peace of the unconditioned mind experienced once the causes of suffering - and causation altogether - have been eliminated. Samsara and nirvana are two fundamental pillars of Buddhist thought and defined as opposites. Especially in the Theravada tradition, Buddhists are trying to free themselves from one to attain the other. The Four Truths therefore embrace both the reality we are in now and the enlightened reality we are directing our lives towards.

You may have noticed a problem with this logic. Surely, if following the Buddhist path is the cause of the cessation of suffering, as this logic indicates, then the cessation of suffering, or nirvana, is produced by causes and is not unconditioned. This is indeed not merely an academic problem of logic, it is a problem that threatens to topple the entire edifice of Buddhist thought. If nirvana is not unconditioned then no transcendence is possible, and there is no way out of the tremendous suffering of conditioned existence. If that were the case, the spiritual path itself would become redundant. After all, if there is no way out, if conditioned existence is all there is, then why bother? We could all give up, go on holiday and have what’s called ‘a good time’.

Even though the path is presented as the cause of nirvana, the relationship between the two is not one of causality as we know it. Nirvana is definitely unconditioned; it is not produced by anything, there is nothing specific one can do to make it arise. That’s why the Buddhist path does not produce nirvana in the normal sense of the word, as though nirvana did not exist before we followed the path and it arose after we followed it. Instead, the function of the path is to clear away everything that prevents us from recognizing and actualizing the state of nirvana that is there already, even before we start on the path. Following the path is a cleansing process that eliminates afflictions and defilements, habits and tendencies, and misunderstandings of reality. Once these are washed away, the state of nirvana will be clearly seen. The change that occurs is not about whether nirvana is there or not; it is about whether we are aware of it or not.

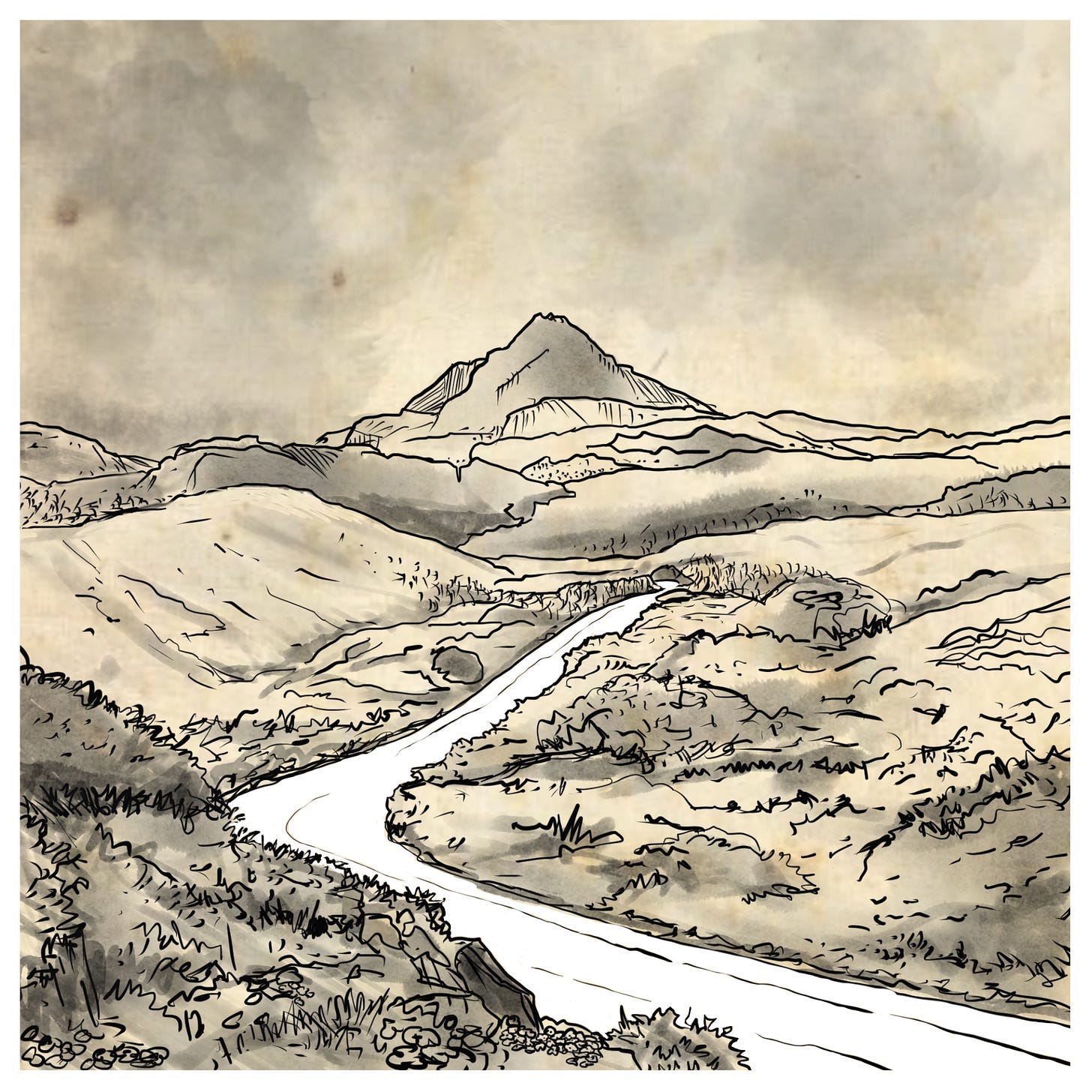

Two images are often used to illustrate the relationship between the path and the result. One is that of a footpath and a mountain. By treading a footpath one can reach a mountain and have an experience of the mountain, but one cannot say that the path created the mountain. The path simply leads to the mountain.

Another image uses the analogy of washing a dirty piece of cloth. Let’s say you play rugby and your white T-shirt is covered in mud. What the washing machine will do is use the method of soap and water to separate the mud from the cloth. The result is a pure white T-shirt; but the washing process did not produce a white T-shirt. The white T-shirt was already there to start with; the mud was only an incidental stain.

The Buddhist path, then, is designed to get rid of everything that gets in the way of our recognizing the ultimate state of nirvana and the true state of our minds. But nirvana is beyond words, it is indescribable, it is by definition beyond anything we experience in ordinary life because it can only be known by the unconditioned mind which is not the mind we use in ordinary life. There is therefore a puzzle right there. Buddhists direct their entire lives towards a goal they cannot comprehend until they get there. Is that stupidity? Wishful thinking? Blind faith? My answer is that it’s none of these because the Buddhist teachings do give a basic understanding of the process involved and through meeting Buddhist masters we can sense for ourselves the sublime reality to which the teachings point. And meditation will give us glimpses of it along the way.

Finally, it’s important to know that the Four Truths are not dogmatic truths and are not the equivalent of the Christian Creed or the Five Pillars of Islam. The word ‘truth’ refers to ‘reality’, the way things are, rather than to truths with which we are free to agree or disagree. These realities apply to everyone, they are not a matter of belief; we discover them through hard experience just like the Buddha did himself, and there is no question of accepting them simply on the Buddha’s say-so. We apply the Four Foundations of Mindfulness and vipasyana meditation to these teachings and test them against our experience and our reason, and that is how they become true for us. So that is another challenge they pose: we need to make some personal effort to explore and assimilate these points and make them our own.

Questions for you to ponder and respond to in the Comments. Comments are open to everyone.

How do you imagine the complete end of suffering? What might that be like?

Do you think that following the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism can ever be compatible with modern culture?

And if you liked this article please tick the like button!

To receive all my posts and support my work subscribe now.

Photo of a painting by David Rycroft. Drawing by Alex Peters.

For more like this see my book Discovering Buddhism https://troubador.co.uk/bookshop/religion-beliefs/discovering-buddhism