One of the slogans behind the French Revolution was these few words by Jean-Jacques Rousseau: All human beings are born free and everywhere they are in chains. This type of thinking is still very prevalent today, I believe, in the sense that there is a pervasive idea that humans are naturally free and innocent but they are prevented from fulfilling their potential by external circumstances. Those circumstances include the political and/or economic system within which we live and, for some, the social and cultural level of organisation as well. It follows that happiness will only be found by changing these systems.

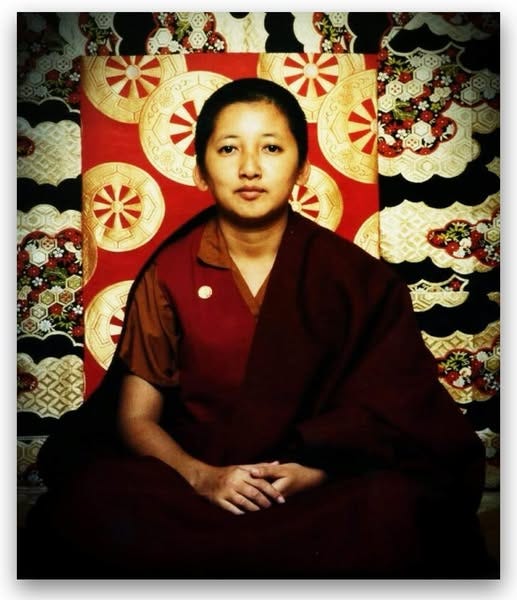

The issue of freedom versus unfreedom can also be discussed in spirituality and specifically within Buddhism. Interestingly, as Khandro Rinpoche recently noted in Berlin, it’s quite common for Westerners coming to Buddhism to believe that there should be no discrimination at all in the spiritual domain. After all, didn’t the Buddha teach that we are all equal in that every single one of us has the spark of an enlightened nature inherent in our being? If we accept this then we should treat everyone equally and there really is no basis for categorising and differentiating groups or types of people on the Buddhist path.

Indeed, our shared enlightened nature is one of the main arguments in favour of compassion for all.

This egalitarian approach manifests within Buddhist communities every day. Quite commonly I come across people who resent hierarchical structures of any kind. I also know many people who don’t accept the principle of a staged and gradual path and who want access to the highest teachings straight away. They don’t see why they should practise meditation and preliminary practices for years before they can get the real deal in ‘higher’ teachings. They believe that everyone should have equal access to everything. To be told otherwise is experienced as a harsh judgement of who we are as a person: that we are not good enough, not advanced enough, that somehow we don’t have the potential. Whatever the form of differentiation between people on the Buddhist path, does this not contradict the very basis of the Buddha’s teachings?

Rousseau’s thinking easily gets transposed to the Buddhist world, which means that those with egalitarian inclinations will lay the blame for any restrictions on the Buddhist organisation in question. Suddenly, Buddhism is accused of becoming institutionalised – like a religion – and those with responsibility within that institution might be demonised and blamed for such unfair practices as establishing requirements for access to certain courses. Similarities with the university system, where one cannot enrol for a doctorate before one has completed a batchelor’s or master’s degree, are thrown out as irrelevant. Spirituality, it is claimed, is quite different. It is, by definition, the domain of ultimate freedom which also means freedom from imposed constraints and from conceptualisation of any kind. And the spiritual process is not as linear as a curriculum would have us believe.

So, in Tibetan Buddhism specifically, we are confronted with the paradox of the buddha nature on the one hand which is equally present in everyone, and structural distinctions between the Vehicles of Buddhist teachings and even, within each of those Vehicles, the classification of students according to lower, middle and higher potential. So how does the tradition account for this?

According to the Great Perfection teachings, we are all enlightened buddhas already. Zen teachings will similarly state that enlightenment is present in us right now, it is not some far-off state that takes aeons to attain. At the same time, the Great Perfection also asks us to acknowledge that we are not perfect. We don’t understand everything in breadth and depth like a buddha, we don’t always know what choices to make, we sometimes get caught up in emotional reactions and some of us have an attention span of only 30 seconds which looks rather different from samadhi concentration. So how is it possible for perfection and imperfection to exist side by side?

Equal and not equal

Buddhism, too, laments the fact that everyone everywhere is in chains but here they are metaphorical chains, they are factors that limit and determine the way our minds function. In the Buddhist analysis, what prevents us from embodying our naturally inherent enlightened freedom is nothing external; it is the mental afflictions, the destructive emotions that cause our own distress and ill-health and that lead us to act in ways that cause harm to ourselves and others, as well as to the environment and the world; and the misunderstandings we have about who we are and how life is. These factors are together called obscurations because they prevent us from seeing that enlightened nature within. They are the reason we don’t know who we really are; they explain all the cognitive distortions that stop us from seeing reality as it is.

The Buddhist path is about working with these obscurations, and only that. The path itself is not about our enlightened nature because that is a given, it is the foundation of our existence. What the path sets out to do is purify the obscurations and eliminate them so that our enlightened nature can be recognized and fully realized. The path is not about gaining anything, it is about losing all the baggage that gets in the way.

Khandro Rinpoche made it very clear that all the distinctions that are made between Vehicles and between types of student are based on the obscurations. They are never, and cannot be, based on the buddha nature that is present in all. For anyone familiar with the Buddhist teachings this point might seem quite obvious and yet it was not so clear to me before Khandro Rinpoche stated it.

Any differences in acumen are due to whether a person’s obscurations are powerful, less powerful or tamed. And since the rationale of the path is to work with obscurations, it follows that different methods and approaches might be necessary according to the type and intensity of obscuration that presents.

No contradiction

Buddhism avoids the contradiction highlighted by Rousseau’s words by distinguishing ultimate and conventional truths. We are all equal in ultimate truth but each one of us carries a unique set of obscurations in conventional truth. In other words, we are speaking of two different dimensions of reality, not two contradictory states of affairs that exist, and can be compared, on the same plane. Our enlightened nature is enduring, no matter what, whereas our obscurations are temporary and can be eliminated.

In summary, then, the Buddha invites us to turn our attention inward. We will not find the root causes of our unhappiness in external situations as such, we will find the causes within our own minds. It would therefore be a mistake to lay the blame for situations we don’t like at the feet of other people or the systems they have created. Of course, to really understand the logic here one needs to study Buddhist thought a bit. Let’s say that current circumstances are often beyond our control whereas we do have the power to transform our minds. And if we act from a tamed mind where the obscurations no longer lead us by the nose, then whatever actions we do will have the power to bring benefit.

Very clearly formulated - it indeed helped to remind myself again that it is all about purifying obscurations! Thanks for taking the time to process Jestun Khandro Rinpoche's teachings like this 🙏🙏🙏

This explains a question I’ve had since I began to embrace Buddhism. I’ve studied various lineages and traditions. I finally put my cushion down when I found Pure Land. I continue to read and learn from various teachings but I seem to resonate most with simplicity. Some teachers are so advanced I end up down a metaphysical rabbit hole. This was very well presented and I enjoyed reading it. Thank you 🙏🪷