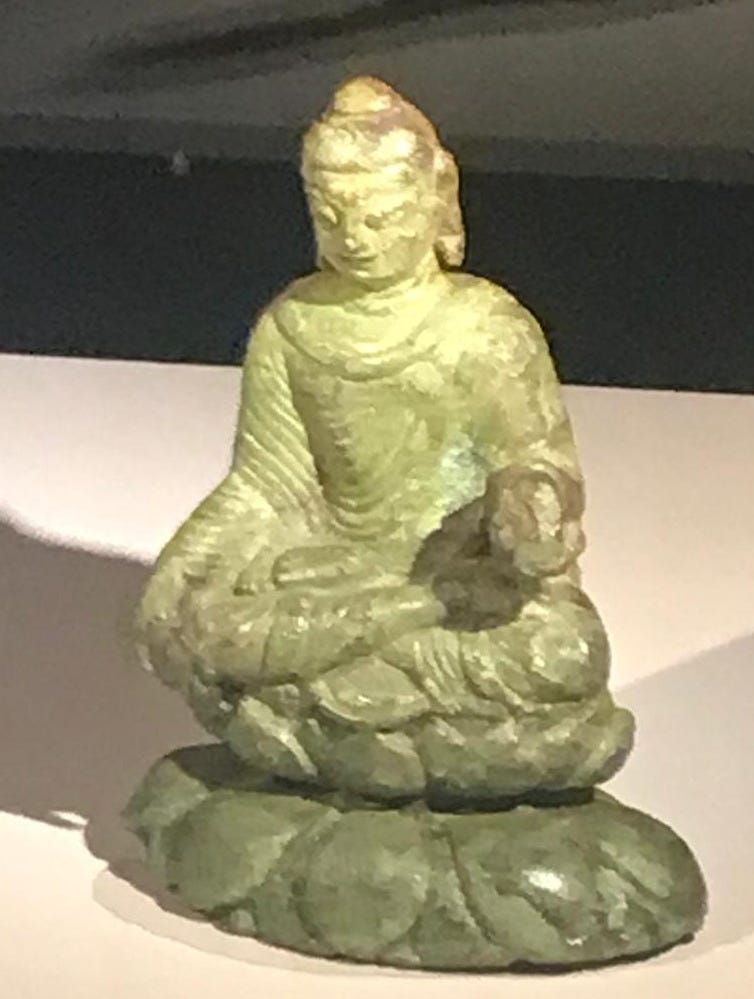

This photo shows a small bronze buddha figure, beautifully preserved. It is the first object we meet on our journey through the Silk Road exhibition at London’s British Museum, and in a way it tells the whole story behind this event, the story of a vibrant interconnected world that spanned almost two millenia. This buddha is not just a drop in the ocean of exceptional artefacts gathered together here, rather it is the ocean in a drop.

It was probably made in the Swat Valley, in present-day Pakistan, where Buddhism and its art and sculpture flourished for just under a thousand years between approximately 200 BCE and 800 CE. This piece was probably made in the late 500s. Interestingly, it was unearthed 5000 kilometres away on the tiny Swedish island of Helgo near buildings dated to 800 CE. Its discovery dramatically broadened our understanding of the Silk Road, demonstrating a complex network of many roads that stretched from East to West and that branched off to the north and south. We …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to the softer gaze to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.